Wearing a light-colored jacket, dark trousers and sunglasses, the 12-year-old boy is led onto the stage of the legendary Apollo Theater in Harlem. He is taken to sit on a chair, the microphone is adjusted to his height, and bongo drums are placed into his searching hands. The year is 1963, yet hardly anyone in the theater knows who “Little Stevie Wonder” is when his record label Motown Records introduces him.

His fingers fly effortlessly over the bongos, and he appears both touchingly innocent and lost in his own world. Little Stevie sings a few “yeahs” into the microphone, asks the audience to clap their hands, stomp their feet, jump up and down, or do anything they want to do. The bongos are replaced by a harmonica, and the gangly boy, accompanied by a Big Band, peps up the audience with a lot of gusto. “Fingertips” is the name of this first single, which the 12-year-old presents at the Motortown Revue, right after Marvin Gaye’s performance. The jazz instrumental is released as a single and becomes Stevie Wonder’s — and Motown’s — first number one hit on the US charts.

Blinded as a baby

Many child stars break down under the strain of early fame. But not Stevie Wonder: his biography seems to be the natural consequence of his genius. Both his musical abilities and his career were truly a wonder.

Stevland Hardaway Judkins was born six weeks premature, on May 13, 1950, in Saginaw, Michigan. He was given oxygen while lying as an infant in an incubator, but the level was too high. That, along with the prematurity, caused the retinas of his eyes to detach before he could even get a glimpse of his environment. Baby Stevland, the third in a line of six children, was blinded.

When Stevland was four years old, his mother left his father and moved from the suburbs with her children to the car-manufacturing mecca of Detroit. She struggled to take care of her children and survive. Sometimes there was hardly enough money for lunch.

“My mother always told me that I could do anything as long as I was careful,” Stevland once reflected about his childhood and inquisitive nature. He himself never considered his blindness to be a handicap. He climbed trees and rode a bike. Perhaps more intensively than other children, he soaked up music, spending hours listening to the radio, and later, glued to the loudspeakers of the television. He would bang on pots and pans, and taught himself every instrument he could get his hands on. At the age of nine, he could play bongo drums, harmonica, bass, and piano.

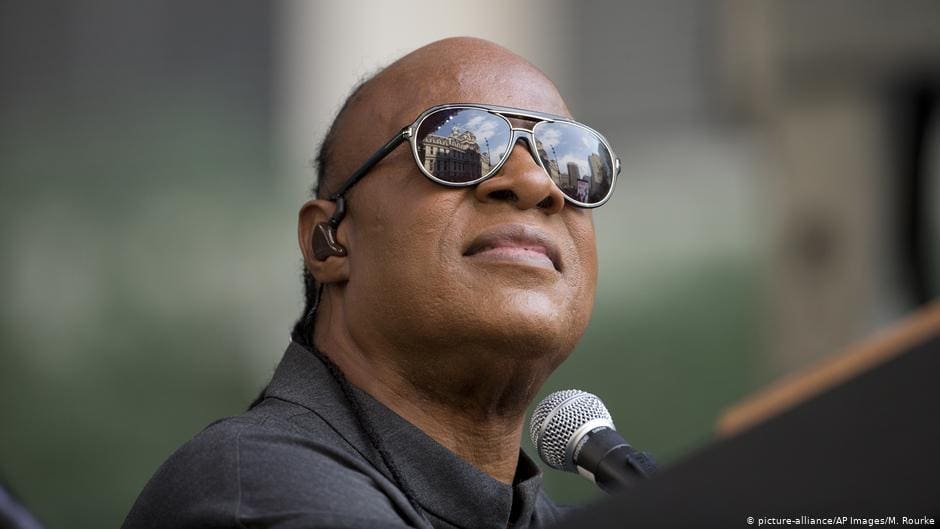

Stevie Wonder in 1975

The Motown miracle

It was in this period that he began performing as a solo singer in a church community, and then caught the attention of a member of the band Miracles, who introduced him to Motown Records. Founded in 1959, the independent label was then rising to become a giant of soul and R&B music by African American artists. For Motown founder Berry Gordy, the little blind boy with the harmonica was a miracle. He signed him on as “Little Stevie Wonder” and paid the tuition for him to attend a private school for the blind.

Not quite 16 years old, his voice having already changed, Stevie Wonder landed the chart hit “Uptight.” One year later, “I Was Made to Love Her” was released. By the age of 18, Wonder had already begun asserting himself with confidence and determination in relations with Motown, composing new albums and singles himself and making his mark on the arrangements, including the still timeless love song “For Once in My Life.” He would later found his own label, Black Bull Music, preferring to do everything himself: composing, singing, playing instruments, recording and producing. His multi-talented versatility made him a legend.

Stevie Wonder is a musician incarnate: He has created a one-of-a-kind sound by mixing soul, gospel, jazz and R&B that would ultimately influence a wide array of musicians, including The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Michael Jackson, Prince and Bob Marley.

The 1970s was a particularly groundbreaking decade for him, in which he practically created his life’s work and his musical legacy. Three exceptional albums were released in quick succession: Talking Book in 1972, Innervisions in 1973 and Songs in the Key of Life in 1976. The songs on them made music history and remain timeless hits today, such as “Superstition,” “Living for the City” and “Isn’t She Lovely?” Wonder was showered with awards during this time, including 14 Grammys.

A hero for African-Americans

At the time, it was primarily to African-American musicians to whom Wonder lent a sense of self-confidence. Yet his musical genius overcame social and race barriers from the very beginning. Although Wonder was black and came from a poor family, white musicians like John Lennon, Eric Clapton and Barbra Streisand considered it an honor to work with him and perform his compositions.

Wonder has always advocated civil rights and protested apartheid. “Living for the City,” for example, addresses the poverty and lack of opportunity among many African-Americans. The British newspaper The Guardian even called the song the “soundtrack of the 70s.”

He dedicated his 1985 Oscar for the song “I Just Called to Say I Love You” from the film comedy The Woman in Red to Nelson Mandela. In 1986, he was able to introduce Martin Luther King’s birthday as a holiday in the US with a human rights campaign and the especially composed “Happy Birthday to You.”

As of 2009, he has been a peace ambassador for the United Nations. “I am always optimistic, but the world is not,” the singer told The Guardian in 2012. “But it takes every single person. And the mindset must change. How is it possible that we still have to struggle with racism today?”

He was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Obama in 2014

A gut feeling

But Stevie Wonder is not only concerned with social injustice and discrimination. Genuinely interested in a wide variety of subjects, he is also always driven by the desire to transform life and its uniqueness into sounds and rhythms, such as the double album he composed for the documentary The Secret Life of Plants in 1979, creating a soundtrack for nature which he himself could never see.

On a personal level, the music pioneer married three times from 1970 onwards, and had nine children from five different women.

The musician has never had an agenda, a master plan. Wonder listens to his gut feeling, his inner life. Whether natural phenomena, love or discrimination — his songs have always had an audible soul. “Somehow I always get to know myself through my music. I ask myself every time, ‘Did I write this?’”

Three more albums followed in the 1980s, but they could not top the success of the 1970s. Wonder then took a long break from making further albums, singing instead the song “Just Good Friends” in duet with Michael Jackson in 1987. He composed the soundtrack to Spike Lee’s 1991 movie Jungle Fever. He spent eight years creating his next solo album, Conversation Peace — his 22nd, released in 1995. The gaps between his albums grew, the next one, A Time to Love, coming out in 2005.

The influential star often appears at award ceremonies. He sings tributes to other fellow musicians, for instance at Michael Jackson‘s or Aretha Franklin‘s funerals, or most recently to Bill Withers who died on March 30.

Even during the coronavirus crisis, the now 70-year-old star remains present on the virtual stage. Wonder’s tribute to Withers was part of the ambitious One World: Together At Home concert, during which different international stars performed a song from home.

As he remembered Withers with a cover of one his best-known hits, “Lean on Me,” Wonder reminded the world that solidarity can help us get through the pandemic: “During hardships like this, we have to lean on each other for help,” he said as he began to play.

Chicagoans join to sing ‘Lean On Me’ in tribute to Bill Withers

This content was originally published here

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our blog.

By continuing, you agree to our use of cookies.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our blog.

By continuing, you agree to our use of cookies.